Recently, I finished the most marvelous book my roommate gave me called Theo of Golden by Allen Levi. If you haven’t read it, I highly recommend. It’s a beautiful story about a generous old man who moves to a small town in Georgia, called Golden, and decides to gift a whole gallery of portraits to their “owners,” or the people they depict.

It’s a story of hope, suffering, and the beauty of “little, nameless, unremembered” acts of kindness.

It also has a gripping ending with multiple twists. I loved it!

Besides being an enjoyable read with endearing characters, an intriguing storyline, and vivid descriptions, this book inspired me as an artist to think more deeply about my portrait work.

What is in a face?

What does it mean to portray someone’s likeness—someone made in the image of God and thought of before the beginning of time?

Allen Levi builds a powerful narrative around the idea that people’s faces reveal deep truths about who they are—their souls, their pain, their longings—and that looking, really looking, at someone’s face is one of the greatest dignities one human being can impart to another. “God gave us faces so we can see each other better.” (p. 259)

Therefore, a portrait by a skilled artist can also be a unique “window” to the soul, and one through which the subject may actually see something in himself which wasn’t plain to him before.

This happens on multiple occasions in Theo of Golden. Without fail, Theo, the old man, tells the subject of each portrait what he sees when he looks at their faces: “…this face belongs to one who is strong and brave and kind. It belongs to one who is capable of saintliness.” (p. 41)

“There is wisdom here, I believe. In the eyes. A young, tender heart; a wise, old soul. That’s a good combination. Wisdom and playfulness. There is the possibility of a saint in this face.” (pp. 170-171)

Theo tries to see them for who they truly are—not an estimation based on status or wealth or education or talent, but on their potential for “saintliness.” When he gifts each one their portrait, he gifts them a little piece of themselves as well, a knowledge of their identities that has been lost, forgotten, or hidden over time.

A portrait is more than a mere representation of someone’s physical likeness.

It is more than a demonstration of artistic skill, however great or small.

A well-crafted portrait is a celebration of the glory of God.

It is a celebration of the subject’s innate dignity as a human being.

It is a reminder that, no matter how ordinary or unremarkable we may feel, we are all worth the intent concentration, detailed precision, and careful attention of an artist.

I think that’s why I never get tired of painting or drawing a face. There is something—some minute, nearly-hidden glimpse of the infinite glory of God—lingering in the sculpt of a nose, the curve of a chin, the spattering of freckles on cheeks. Each one different. Each one sacred.

After all, He meant what He said when He made us in His image.

And maybe if we start looking, really looking, at one another’s faces, we will see something we did not expect.

We may see a glimmer of Heaven.

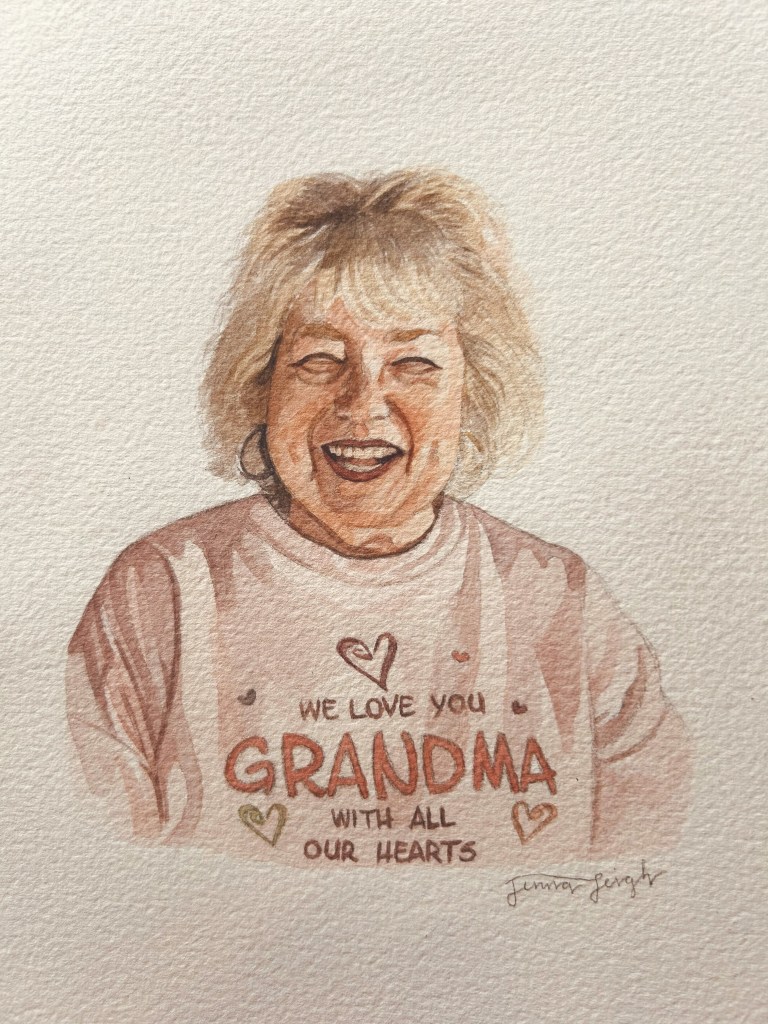

Just before finishing Theo of Golden, I painted a quick watercolor portrait of my Gramma for my mom and her sisters, a few days before the third anniversary of her passing. As I painted, I thought of these things, of how precious faces are, especially the faces of ones we love.

It was strange how each simple line I drew looked and felt so much like her, this face that I love, that I bear a resemblance to. I watched this representation of her come to life on the page, a special keepsake for her children and her children’s children. When we see it, we can remember the warm, rich, happy privilege of knowing her love. We can remember the sound of her laughter, and the way her eyes crinkled when she smiled. We can remember her fierce devotion to those she held dear.

And all this from a face.

“There must be love for the gift itself, love for the subject being depicted or the story being told, and love for the audience. Whether the art is sculpture, farming, teaching, lawmaking, medicine, music, or raising a child, if love is not in it—at the very heart of it—it might be skillful, marketable, or popular but I doubt it is truly good. Nothing is what it’s supposed to be if love is not at the core.” (p. 119)

Leave a comment